Women's fashion

In the 1780s, panniers finally disappeared, and bustle pads (bum-pads or hip-pads) were worn for a time.

By 1790, skirts were still somewhat full, but they were no longer obviously pushed out in any particular direction (though a slight bustle might still be worn). The "pouter-pigeon" front came into style (many layers of cloth pinned over the bodice), but in other respects women's fashions were starting to be simplified by influences from Englishwomen's country outdoors wear (thus the "redingote" was the French pronunciation of an English "riding coat"), and from neo-classicism. By 1795, waistlines were somewhat raised, preparing the way for the development of th

e empire silhouette and unabashed neo-classicism of late 1790s fashions.

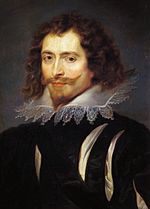

e empire silhouette and unabashed neo-classicism of late 1790s fashions.Gainsborough's 1785 portrait of Mrs Hallett (right) captures the exact transition between the tight bodice and elbow-length, ruffled sleeves of the mid-18th century and the natural waist and long sleeves typical of the 1790s.

Portrait of Mr and Mrs William Hallett by Thomas Gainsborough, 1785.

The usual fashion of the years 1750-1780 was a low-necked gown (usually called in French a robe), worn over a petticoat. If the bodice of the gown was open in front, the opening was filled in with a decorative stomacher, pinned to the gown over the laces or to the corset beneath.

Tight elbow-length sleeves were trimmed with frills or ruffles, and separate under-ruffles called engageantes of lace or fine linen were tacked to the smock or chemise sleeves. The neckline was trimmed with a fabric or lace ruffle, or a neckerchief called a fichu could be tucked into the low neckline.

The robe à la française featured back pleats hanging loosely from the neckline. A fitted lining or under-bodice held the front of the gown closely to the figure.

The robe à l'anglaise featured back pleats sewn in place to fit closely to the body, and then release into the skirt which would be draped in various ways.

Jackets and redingotes

The lady wears strapless stays over a pink chemise. Her petticoat has pocket slits to access the free-hanging pocket beneath. "Tight Lacing, or Fashion Before Ease", 1770-75

Toward the 1770s, an informal alternative to the gown was a costume of a jacket and petticoat, based on working class fashion but executed in finer fabrics with a tighter fit.

The Brunswick gown was two-piece costume of German origin consisting of a hip-length jacket with "split sleeves" (flounced elbow-length sleeves and long, tight lower sleeves) and a hood, worn with a matching petticoat. It was popular for traveling.

The caraco was a jacket-like bodice worn with a petticoat, with elbow-length sleeves. By the 1790s, caracos had full-length, tight sleeves.

As in previous periods, the traditional riding habit consisted of a tailored jacket like a man's coat, worn with a high-necked shirt, a waistcoat, a petticoat, and a hat. Alternatively, the jacket and a false waistcoat-front might be a made as a single garment, and later in the period a simpler riding jacket and petticoat (without waiscoat) could be worn.

Another alternative to the traditional habit was a coat-dress call a joseph or riding coat (borrowed in French as redingote), usually of unadorned or simply trimmed woolen fabric, with full-length, tight sleeves and a broad collar with lapels or revers. The redingote was later worn as an overcoat with the light-weight chemise dress.

Underwear

The shift, chemise (in France), or smock had tight, short or elbow-length sleeves and a low neckline. Drawers were not worn in this period.

The long-waisted, heavily boned stays of the early 1740s with their narrow back, wide front, and shoulder straps gave way by the 1760s to strapless stays which still were cut high at the arm pit, to encourage a woman to stand with her shoulders slightly back, a fashionable posture. The fashionable shape was to have smooth curves, a rather conical torso, with large hips. The waist was not particularly small. Many women's waists measure larger with stays than without. Stays were usually laced snugly, but comfortably; only those interested in extreme fashions laced very tightly! They offered back support, for heavy lifting, and poor and middle class women were able to work comfortably in them. As the relaxed, country fashion took hold in France, stays were replaced by an unboned or lightly boned quilted underbodice (now called for the first time un corset) for all but the most formal court occasions.

Panniers or side-hoops remained an essential of court fashion but disappeared everywhere else in favor of a few petticoats.

Free-hanging pockets were tied around the waist and were accessed through pocket slits in the side-seams of the gown or petticoat.

Woolen waistcoats were worn over the stays or corset and under the gown for warmth, as were petticoats quilted with wool batting, especially in the cold climates of Northern Europe and America.

Shoes

Shoes had high, curved heels (the origin of modern "louis heels") and were made of fabric or leather.

Hairstyles and headgear

The 1770s were notable for extreme hairstyles and wigs which were built up very high, and often incorporated decorative objects (sometimes symbolic, as in the case of the famous engraving depicting a lady wearing a large ship in her hair with masts and sails — called the "Coiffure à l'Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la liberté" — to celebrate naval victory in the American war of independence). These coiffures were parodied in several famous satirical caricatures of the period.

By the 1780s, elaborate hats replaced the former elaborate hairstyles. Mob caps and other "country" styles were worn indoors. Flat, broad-brimmed and low-crowned straw "shepherdess" hats tied on with ribbons were worn with the new rustic styles.

Hair was powdered into the early 1780s, but the new country fashion required natural colored hair, often dressed simply in a mass of curls.

Elijah Boardman wears a cutaway tailored coat over a waist-length satin waistcoat and dark breeches. America, 1789.

Throughout the period, men continued to wear the coat, waistcoat and breeches of the previous period. What changed significantly was the fabric. Under new enthusiasms for outdoor sports and country pursuits, the elaborately embroidered silks and velvets characteristic of "full dress" or formal attire earlier in the century gradually gave way to carefully tailored woolen "undress" garments for all occasions except the most formal.

In Boston and Philadelphia in the decades around the American Revolution, the adoption of plain undress styles was a conscious reaction to the excesses of European court dress; Benjamin Franklin caused a sensation by appearing at the French court in his own hair (rather than a wig) and the plain costume of Quaker Philadelphia.

At the other extreme was the "maccaroni".

Coats

The skirts of the coat narrowed from the gored styles of the previous period, and toward the 1780s began to be cutaway in a curve from the front waist. Waistcoats extended to mid-thigh to the 1770s, and gradually shortened until they were waist-length and cut straight across. Waistcoats could be made with or without sleeves.

As in the previous period, a loose, T-shaped silk, cotton or linen gown called a banyan was worn at home as a sort of dressing gown over the shirt, waistcoat, and breeches. Men of an intellectual or philosophical bent were painted wearing banyans, with their own hair or a soft cap rather than a wig.

A coat with a wide collar called a frock, derived from a traditional working-class coat, was worn for hunting and other country pursuits in both Britain and America.

Shirt and stock

Shirt sleeves were full, gathered at the wrist and dropped shoulder. Full-dress shirts had ruffles of fine fabric or lace, while undress shirts ended in plain wrist bands. A small turnover collar returned to fashion, worn with the stock. The cravat reappeared at the end of the period.

Breeches, shoes, and stockings

As coats became cutaway, more attention was paid to the cut and fit of the breeches. Breeches fitted snugly and had a fall-front opening.

Low-heeled leather shoes fastened with buckles, and were worn with silk or woolen stockings. Boots were worn for riding.

Hairstyles and headgear

Charles Pettit wears a matching coat, waiscoat, and breeches. Coat and waistcoat have covered buttons; those on the coat are much larger. His shirt has a sheer frill down the front. America, 1792.

Wigs were worn for formal occasions, or the hair was worn long and powdered, brushed back from the forehead and clubbed (tied back at the nape of the neck) with a black ribbon.

Wide-brimmed hats turned up on three sides called tricornes were worn in mid-century. Later, these hats were turned up front and back or on the sides to form bicornes. Toward the end of the period a tall, slightly conical hat with a narrower brim became fashionable (this would evolve into the top hat in the next period).